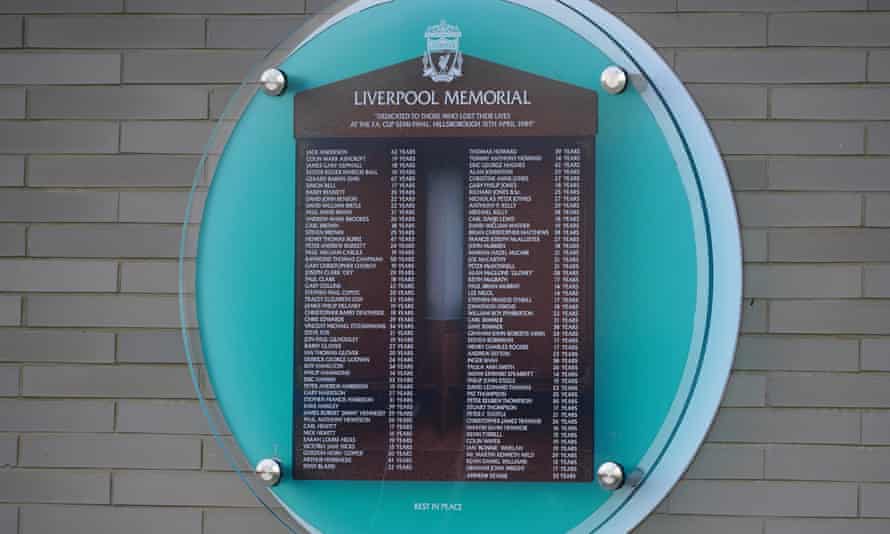

On a grey morning in May this year, the English legal system’s epic failure to secure justice for the families devastated by the Hillsborough disaster finally ground to its dismal conclusion. Ninety-seven people were killed due to a terrible crush on an overcrowded terrace at the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest at Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough football stadium on 15 April 1989. Since then, the families have endured a 32-year fight for the truth to be accepted – that the main cause of the disaster was police negligence, and for those responsible to be held accountable.

The first bereaved parents I met when I began reporting on the disaster and the families’ implacable campaign for justice, in 1996, were Phil and Hilda Hammond, whose son, Philip, had died at Hillsborough, aged 14. Hilda, who worked as a senior intensive care nurse at Liverpool’s Walton hospital, told me that, unbearable as their loss was, she had still been able to understand that disasters can happen. She expected that the authorities would hold prompt and rigorous proceedings. “I thought they would find the truth of how Philip died, how they all died, and if anybody was found to be to blame they would be punished,” she said. “I was so naive.”

Instead of committing to a process that would lead to justice for the people who had died, their families and those who were injured, South Yorkshire police mounted a campaign of lies, and the courts, through a series of proceedings, piled on more trauma.

The people who died at Hillsborough were trapped against a high metal fence at the front of the Leppings Lane terrace, the kind built at many grounds to prevent people invading the pitch, in an era when hooliganism by a minority of thugs led to the demonisation of all football supporters. Behind the fence, railings divided the terrace into a series of “pens”. Built to enable greater police control of supporters, when the pens were overcrowded they became iron cages from which there was no escape.

When Lee Nicol, 14, died two days later, 95 people had been killed. Then in 1993, Tony Bland, 18 when he went to the match, became the 96th when his life support was turned off. In July 2021, Andrew Devine, who was 22 at Hillsborough, died 32 years after suffering brain damage in the crush, and was certified to be the 97th fatality.

The lies began even as people were dying. The police officer in command, Ch Supt David Duckenfield, failed to take control of the chaos and organise a concerted rescue operation, but he started the false narrative that would form the foundation of enduring injustice. In an episode still profoundly shocking decades on, at 3.15pm Duckenfield lied to the Football Association official, Graham Kelly, telling him that Liverpool supporters had forced open a gate, and rushed into the Leppings Lane end of the ground. That story was given to the media and at 3.25pm, John Motson reported in a live BBC broadcast that a gate was said to have been broken down, and that non-ticket holders had forced their way in. Right away, the victims were being blamed for their own deaths and injuries.

The South Yorkshire police chief constable, Peter Wright, admitted hours later that the gate had not been forced open – Duckenfield himself had given the order for it to be opened. The police had failed to organise a safe way for the 24,000 Liverpool supporters to access the stadium, through the nasty, obstacle-strewn bottleneck approach to the turnstiles at the Leppings Lane end. Congestion built up at those entrances, then at 2.52pm Duckenfield ordered a wide exit gate to be opened, to relieve the pressure by allowing many people into the ground at once. About 2,000 people then came in together, and most headed down a tunnel facing them that led straight into the already packed central pens. If Duckenfield had ordered officers to close access to the tunnel and direct people to the side pens where there was still room, the crush would have been avoided. Yet despite Duckenfield’s original story being exposed as a lie, the police nevertheless constructed a case that Liverpool supporters caused the dangerous situation outside the ground, by arriving without tickets, late, drunk and misbehaving.

The essential truth was established by Lord Taylor just four months after the disaster, in his report after the official inquiry. He concluded that the main cause of the disaster was “the failure of police control”, and described Duckenfield neglecting to close off the tunnel after ordering the exit gate to be opened as “a blunder of the first magnitude”. Taylor severely criticised the South Yorkshire police for failing to accept responsibility and pressing a false case against the victims. Yet even then, the police advanced the same allegations at the inquest the following year, and all the legal proceedings that followed, in which the families sought the truth and justice for their loved ones.

The legal system that dragged bereaved families through 32 years of adversarial battles finally concluded its work in May. The result is that nobody has been held accountable for 97 people dying, nor for the police campaign of lies designed to shift blame on to the victims. The families and their advocates are now calling for reform, for a “Hillsborough law” and a public advocate to repair some of the system’s worst injustices. Valuable as that will be, when you consider the whole ordeal, it makes the case for a complete overhaul.

On the weekday night 25 years ago that I first met Phil and Hilda Hammond, Hilda just back from work in her nurse’s uniform, we sat around the kitchen table for hours at their immaculate semi-detached home in Aigburth, south Liverpool. Their younger son Graeme, still a teenager, popped in and out, as his parents related the events that devastated their family. Phil, a post office manager, was vice-chair of the Hillsborough Family Support Group (HFSG), at the forefront of the struggle for justice. When I asked what their son Philip was like, Phil grimaced, his face reddened; he said he struggled to talk about him. Then they did tell me about Philip’s talents, his leadership qualities, enthusiasm for sport, how well he was growing up. Eventually Phil said simply: “He was a great lad, a great person to know.”

They talked about the unbelievable shock of his death, the pain of the police lies, the poison published by the Sun under the headline “The Truth”, the betrayal by the West Midlands police, which was appointed by South Yorkshire police to investigate the disaster. They recalled the nightmare daily slog to Sheffield for the inquest – the legal process to determine how, when and where a person has died where there is some doubt or issue of public concern. The South Yorkshire coroner, Dr Stefan Popper, gave serious credence to the police allegations against the victims. Bereaved families had no right to legal aid funding and could afford only a single barrister, who was outnumbered by those representing the police, who were paid for using public money. In March 1991, the jury returned a verdict of accidental death. The Hammonds, and all the families, felt it was a grievous miscarriage of justice.

I wrote about these travesties in a 1997 book, The Football Business, contrasting football’s escalating fortunes after the disaster with the families’ abandonment to a terrible fight that prevented them from rebuilding their lives.

In the same year, Prof Phil Scraton, the principal academic expert on the Hillsborough injustice, exposed that South Yorkshire police had an operation to amend officers’ accounts of the day to minimise criticism of senior officers. Yet despite that scandal and more revelations, years passed, into the bleak 00s, with the justice campaign building strongly in Liverpool but too little media coverage, and nothing solid moving for the families.

The 20th anniversary wasn’t news, it was just a dreadful landmark, but one the media would cover. I was working for the Guardian by then, and was determined that we would use the moment to highlight the enduring injustice. My article, published on 13 April 2009, focused on the issues the Hammonds had outlined 13 years earlier, the amendments to South Yorkshire police officers’ statements, and deepening concerns about the role of West Midlands police.

I went to see Anne Williams, whose son Kevin, 15, died in the crush, and who pursued repeated challenges to the Popper inquest. Maria Eagle, the Merseyside MP who had made an excoriating speech in parliament in 1998, accusing South Yorkshire police of running a “black propaganda unit” to shift blame on to the innocent victims, stood by this view, and we ran that on the front page.

On the morning we published, Andy Burnham, then Labour’s culture secretary, called me to say he had read it, and had resolved to do something to address the injustice. He had formed the view that if the South Yorkshire police and other authorities published all the documents they held in their files, it could break the legal deadlock. Two days later, he addressed the memorial service at Anfield, attended by 30,000 people. As Burnham read a statement from the prime minister, Gordon Brown, that expressed sympathy but did not address the injustice, he was interrupted by calls from the crowd, for justice.

Confronted with that strength of feeling, Brown’s government finally understood that this was an unresolved scandal, and gave Burnham support for his initiative. The Hillsborough Independent Panel was formed, tasked with producing a report, for publication, that would set out what the documents added to public understanding of the disaster and its aftermath. South Yorkshire police and the families agreed to participate with the panel as constituted, after the families had held out for Scraton to be on it. Paul Leighton, recently retired as deputy chief constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, was appointed as the police expert, Dr Bill Kirkup as the medical expert, and James Jones, the bishop of Liverpool, as chair.

The panel presented its report, after two and a half years’ work, on 12 September 2012, beneath the soaring vaults and gleaming light of Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral. The families were given the report first, with an explanation from Scraton and Jones of how completely the evidence had vindicated their struggle. Then the prime minister, David Cameron, made a double apology in parliament: for the police failings that caused the deaths, and the changed police statements that had contributed to denying them justice.

It was a momentous breakthrough. Many people affected still refer to it as “truth day”. Walking through Liverpool that night, I met survivors hugging one another in disbelief, cradling the 395-page report as if it were a holy book.

The Independent Office for Police Conduct launched its biggest investigation, in October 2012, into the campaign of victim blaming and alleged cover-up. A new police investigation, Operation Resolve, was also mounted into how the disaster had happened, and whether any criminal charges should be brought.

In December 2012, three high court judges took just an hour to quash the verdict of the inquest the families had campaigned against to no avail for 21 years. In a dark, cramped, wood-panelled courtroom in the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand, the lord chief justice, Igor Judge, lamented the “falsity” of the South Yorkshire police campaign to blame the victims and how “disappointingly tenacious” it had been. He criticised Popper’s conduct of the inquest, and stated that, after Taylor’s August 1989 conclusions that failure of police control had been the main reason for the disaster, “That should have been that”.

Judge said the changing of the police statements seemed “reprehensible” and referred to them as “efforts made by some of the authorities to conceal evidence”. He ordered a new inquest to be held, in effect calling for the truths established by Taylor, and now by the panel, to be accepted. “We should deprecate this new inquest degenerating into the kind of adversarial battle which … scarred the original inquest,” he stated, in his written legal judgment.

It was a great landmark, an extraordinary victory for the families. But in that courtroom, it all still felt a very long way from good enough. There was a self-satisfied air around the room and among the judges, in their wigs and gowns on the raised platform. But this represented a monumental failure of their system. The families, bereft, had been forced to fight this unequal battle that had robbed them of so many years.

In that long span of time, family members had suffered, many had become ill, some had died. Phil Hammond, HFSG chair by then, had banged his head on a shelf in the group’s office in 2008, and suffered a near fatal brain haemorrhage. Hilda had had to give up her job to help nurse him. Margaret Aspinall, whose son James, 18, had died at Hillsborough, had taken over as the chair.

Anne Williams had been one of the family members who had applied for the inquest to be quashed in 1993. Now she was brought to the Strand by her brother in a wheelchair, having been diagnosed with cancer just after the panel reported. She had promised herself that when she eventually won her fight, she would live a little, but she died four months later, never seeing the new inquest for Kevin that she had sought for all that time.

Even before the new inquest fully started in March 2014, the families were made to understand that lord chief justice, Lord Judge’s comment, that it should not become another adversarial battle, had no legal power. Duckenfield’s barrister, John Beggs QC, and lawyers for other former senior police officers and junior officers in the Police Federation, stated at a preliminary hearing their intention to argue yet again that Liverpool supporters’ drinking was a factor in causing the disaster.

The law had no mechanism to enable the call by Judge, the head of the judiciary, to be heeded. Court proceedings start with the illusion, for a new jury, that no facts or conclusions have ever been established before. South Yorkshire police officers and their lawyers came to the new inquest and rolled out the same discredited case against the victims. Adversarial battle, and the hurt and scars it inflicts, are what the English legal system provides.

It has a chance of working only if there are equal forces doing battle. This time, the families had their own battalions of lawyers to fight back. The new inquest, presided over by Sir John Goldring, was held under article 2, the right to life, of the European convention on human rights. Incorporated into British law as the Human Rights Act 1998 by the Labour government, its more enlightened provisions allow for bereaved families to have “exceptional funding” for lawyers at an inquest, if the state may have been at fault for the deaths.

The families, for the first time, had enough committed solicitors from some leading law firms specialising in human rights, including Birnberg Peirce and Bindmans. In Liverpool, solicitor Elkan Abrahamson, of Broudie Jackson Canter, had represented some families for years, including Williams, for no payment. Now his firm was funded to steward 22 families through this next battle. The barristers, led by Michael Mansfield QC and Pete Weatherby QC, were rigorous, experienced at fighting miscarriages of justice, and not shy of accusing police officers of lying.

They argued successfully that the families had to be at the heart of the process this time, so the inquest opened with bereaved relatives making personal statements about their loved ones, telling the court about the people whose deaths were the subject of the evidence. This has since become a humanising force in our system, with family statements made at inquests and inquiries, including those for the victims of the Grenfell fire, and the Manchester Arena bombing.

The families’ loving, detailed reminiscences were shattering. They recalled the men, women and many children whose disastrous misfortune it was to be in those vile pens. They remembered their characters, sense of humour, friendships, schooling, careers, interests, religious observance, how much they loved them, how much they missed them.

Steve Kelly, speaking about his older brother Michael, 38, set the tone. In a deep, controlled voice, he told the silent room that his brother was “our Mike”, not just a number, one of the 96. “I have come here to reclaim him,” he said.

Mary Corrigan said of her son Keith McGrath, 17, that when he was born “a love I had never experienced before surged out of me for him”. When Keith died, she said, “a part of me died”.

They told some funny stories too. Brenda Fox recalled that on her son Steve’s 21st birthday his colleagues at the chocolate factory had chucked him in a vat of the stuff. The next day, she brought a picture in to show everyone, of Steve standing dripping in the chocolate, with a rueful smile on his face.

Jenni and Trevor Hicks talked about their teenage daughters, Sarah, 19, and Vicki, 15, and the total impact of their loss. Three sets of brothers also died: Nick and Carl Hewitt, Kevin and Christopher Traynor, Stephen and Gary Harrison. A father and son, Thomas Howard and Tommy Jr, died next to each other.

The contours of the loss were mapped: the youngest to die was Jon-Paul Gilhooley, 10. The oldest was Gerard Baron, 67, a war veteran then a Royal Mail employee. Thirty-seven teenagers had died. Twenty-five of those who died were fathers; 58 people lost a parent. Three babies were born after their fathers died at Hillsborough. One woman, Inger Shah, was the single mother of two teenagers, Becky and Daniel. After she died, they had to be taken into care.

Then, after all these cherished memories of the 96 were heard, the police and their lawyers reheated the long-discredited allegations against the victims, and adversarial battle commenced.

The families’ lawyers fiercely challenged every allegation, depicting the false narrative as a cover-up orchestrated from the top of the South Yorkshire police. A very obvious feature of the disaster became steadily apparent: the police had told their stories, but the whole day had been filmed and photographed. Hundreds of photographs of the crowd were shown on the court screens, and BBC and CCTV footage played repeatedly. It showed congestion at the too-few Leppings Lane turnstiles started at 2.15pm, 45 minutes before the scheduled kick-off, not “late”, the police doing nothing effective to address it until the panicked opening of the exit gate, the people walking through, the open tunnel straight ahead. The inquest addressed in unbearable detail the horrific crush that followed, the piles of bodies at the front of pen 3, how people died, of compression asphyxia. The chaos of the police response was clear, and the heroic efforts of supporters who emerged from the pens then did their best to help, running with dead and injured people placed on advertising hoardings because only two ambulances came on to the pitch.

In all the film and photographs, Liverpool supporters were not misbehaving, and nobody was carrying a drink. Many survivors came as witnesses; they included off-duty police officers, doctors and nurses, and the humanity of the people who suffered made the police portrayal of them as an out-of-control mob look cruel, and evidently false.

Then Duckenfield crumbled as a witness. He admitted he had not done sufficient preparation, did not know the basic layout of the ground, did not take effective action to enable 24,000 people to get through that bottleneck in time and ultimately, that in the crucial moments after ordering the gate open, he “froze”. He admitted when questioned by his own barrister, that his “serious professional failures” had caused the deaths of the 96.

The jury returned their verdict on 26 April 2016. They determined that the 96 were unlawfully killed, due to gross negligence manslaughter by Duckenfield, to a criminal standard of proof – beyond reasonable doubt. And they concluded, having been explicitly asked the question, that no behaviour of Liverpool supporters had contributed to the dangerous situation at the ground. The truth was accepted, and the families, their loved ones, survivors, all the victims, were finally vindicated.

The Guardian’s front page the following morning had a picture of some family members – Brenda Fox, mother of Steve, in the centre – standing in the sunshine outside the court building, arms aloft, singing You’ll Never Walk Alone, Liverpool’s anthem of hope and endurance. Above was the headline: “After 27 years, justice.”

Many families have since lamented how much better it would have been if that could have stood as the end of the ordeal. Yet if 96 people have been unlawfully killed, and the accounts given by a police force and its officers wholly disbelieved by a jury, the system has to provide some accountability.

But the system is not coherent. It does not adopt the conclusions and facts as established by one legal process, and determine how to hold accountable the people and organisations whose fault has been proved. Every stage is entirely separate. To seek accountability, the law moved to criminal prosecutions – a wholly new set of proceedings.

The Crown Prosecution Service, the public authority responsible for bringing criminal cases, charged Duckenfield in June 2017 with gross negligence manslaughter. The former Sheffield Wednesday secretary and safety officer, Graham Mackrell, was charged with safety offences. Sir Norman Bettison, a South Yorkshire police inspector at the time, who later became chief constable of Merseyside police, was charged with misconduct in a public office, but that prosecution collapsed in 2018. Two other former South Yorkshire police officers, Ch Supt Donald Denton and Det Ch Insp Alan Foster, and the force’s then solicitor, Peter Metcalf, were charged with perverting the course of justice, by having the officers’ accounts amended.

The facts of how the 96 were killed were, by definition, exactly the same as those the inquest jury had heard. But Duckenfield’s trial, which began in January 2019 at Preston crown court, would be conducted in front of a new jury, with the facts up for grabs again. The families found themselves on the sidelines again, spectators to an English court and its ceremonials: wigs and gowns, the judge, Sir Peter Openshaw, in red robe, the royal coat of arms, dating back to 1399, on the wall behind him.

Victims and their families in a criminal trial have no right to legal representation, and very limited participation in the process. “The Crown” is still the prosecutor. The family members who did regularly attend in the downstairs gloom of court No 1 at Preston – Jenni Hicks, Christine Burke, whose father, Henry, 46, was killed at Hillsborough, and Louise Brookes, who lost her older brother Andrew, 26, were regulars – sat in seats for the public, separated from the main court area by glass screens. Margaret Aspinall described it as “horrible, like we families were in the dock, not Duckenfield”. Like many, she chose mostly to attend a live broadcast in Liverpool, at the council’s Cunard building. An effort was made there to make the families comfortable, with a small room where they could sit, and have tea and biscuits.

The CPS had appointed Richard Matthews QC, an expert on health and safety and gross negligence manslaughter, to lead the prosecution. Very quickly, families became alarmed by the way he presented the case, and the direction it took.

Despite a 30-year fight for justice, Duckenfield’s barrister, Ben Myers QC, was able to advance the same case the inquest jury had rejected three years earlier, that supporters created the dangerous situation outside the ground because many arrived without tickets, late, had been drinking, and did not comply with police orders. The families’ lawyers had successfully challenged it all at the inquest, but now, Matthews barely contested it at all.

The families had to watch as the conclusions of the inquest were ignored. On 13 February 2019, a former South Yorkshire police officer, Insp Stephen Ellis, broke down while recalling people heading down the tunnel to the central pens after the exit gate was opened. The court took a break, during which Matthews and Myers agreed to have some of Ellis’s 1989 statement read, instead of him having to continue giving evidence. This meant whatever was read would stand as evidence, unchallenged by the prosecution.

But the sections agreed included severe allegations against supporters; Ellis had stated that supporters had been drinking, were pushing, that they were “gripped by a mania” to get into the ground at any cost, that fans had dived over turnstiles to get in. There was a great deal of similar police evidence, not borne out by the video footage, and the families’ lawyers at the inquest had challenged every officer who made such claims, including Ellis.

In response to my questions after the trial, the CPS explained that it couldn’t challenge the evidence due to the rules of court. The Crown had a duty to “prosecute the case fairly and call a cross section of witnesses”, the CPS said, which included calling police officers to give their account of what happened. According to the rules: “The prosecution is not permitted to ‘challenge’ the evidence of its own witnesses.”

So a series of police officers, called by the prosecution, gave evidence that had been discredited at the inquest, and the prosecution allowed it to stand. The families, having fought 30 years against this narrative, made their views known very directly, urging Matthews to fight harder, and the atmosphere became fraught.

Stephanie Conning, a regular attender in Preston, is a survivor, having been at Hillsborough aged 18 with her older brother Rick Jones, 25, and his partner, Tracey Cox, 23, who both died in the crush. They were among those who were outside the ground at 2.52pm and came through the exit gate when the police opened it. She told me: “It has always been traumatic to have these accusations made against us, against our loved ones, and it has taken a great toll on the families to have to fight this, for so long. But we’ve also seen this can work on a jury, and it’s maddening that the CPS won’t challenge it.”

The families also had concerns that Openshaw was sympathetic to Duckenfield. The judge allowed him to sit in the court with his lawyers, rather than in the dock, where accused people routinely sit, isolated, to be studied by a jury. Openshaw later explained in a ruling that this was part of making allowances for Duckenfield’s mental health, including post-traumatic stress disorder. But such a concession to a defendant is rare. Sitting next to his solicitors, wearing his dark suit, made Duckenfield appear less like the accused, more like a victim himself. Myers played hard on that impression, portraying Duckenfield as a pitiful old man who had been “hounded” for 30 years, and was being made a scapegoat for wider failings.

“Just look at him!” Myers pleaded with the jury during his closing speech.

In his summing up, which began on 21 March 2019, Openshaw solemnly recited as credible evidence all the allegations of supporters drinking, not having tickets and being late, including Ellis’s evidence of supporters’ “mania”. But the judge also added his own explanation about Duckenfield’s lie. He suggested to the jury that it had not been a lie at all. As the crisis at Hillsborough was developing, before Duckenfield ordered the exit gate open, two other police officers had briefly said in Duckenfield’s hearing, mistakenly, that a gate had been forced. The judge told the jury that Duckenfield may have genuinely formed that impression himself, and it was “not at all surprising”.

It was, after everything, still a shocking experience to hear Openshaw say that. Everybody in the courtroom – except the jury – knew that Duckenfield himself had always admitted that he lied, as far back as the Taylor inquiry, where he had apologised for it. Yet in that Preston courtroom, everybody was powerless to say anything. Journalists are prohibited, while a trial is proceeding, from commenting or writing anything other than reporting what is said in court that day. My work on the disaster had always involved investigating the past miscarriage of justice, the first inquest, but this was a new feeling, of being trapped in a miscarriage of justice as it was happening.

The families had to endure it, silently, in the public seats. I saw Jenni Hicks during a break, near the top of the dark curved steps up to ground level. She said listening to Openshaw’s summing up was rolling the years back, like sitting through Popper’s travesty all over again. “I feel like I’m back in 1991,” she said.

After eight days considering their verdict, the jury returned to say they could not reach the required minimum majority of 10-2. Matthews immediately told Openshaw he would be applying for a retrial.

Over the summer, some families held a heated meeting with senior CPS officials, protesting at Matthews’s handling of the case, and saying Openshaw should be asked to withdraw. The CPS say they took advice about the judge and decided not to make such an application. They told families they were making improvements to their case, and urged them to remain positive.

So the retrial began on 7 October, in the same court, with the same barristers, and Openshaw still presiding. Everybody had to stand again and bow when he walked in. Some differences were made in the CPS presentation of the case, but broadly it followed the same pattern: Myers and individual police officers alleged yet again that supporters misbehaved outside the ground, Matthews barely challenging that narrative.

This time, on 28 November 2019, the jury, having done their civic duty of assessing what was presented to them, acquitted Duckenfield.

Perhaps as they left the court the jury members saw the incensed reaction of the families, finally released from their enforced silence, Jenni Hicks, Christine Burke and Louise Brookes raging in interviews under TV lights. Only then could the previous findings be reported again, so perhaps the jury members learned for the first time about the inquest determinations, and the new legal position their verdict had established. Ninety-six people had been unlawfully killed due to Duckenfield’s gross negligence manslaughter, and the victims, Liverpool supporters, were fully vindicated. But now, Duckenfield was not guilty of the criminal offence of gross negligence manslaughter, and the police accusations against the victims had been reinstated.

The venue for the last act in the legal system’s Hillsborough saga could look like a cruel, knowing joke. Hilda Hammond told me years before that the stage-managed moves of the Popper inquest were “like going to the theatre”. Now, due to Covid requirements, the concluding trial, of Metcalf, Denton and Foster, charged with perverting the course of public justice, started on 20 April in an actual theatre: the Lowry in Salford.

The families who attended – Jenni Hicks and Christine Burke, with her daughter Cherine, were regulars – were given seats in the upper circle. The judge, Mr Justice William Davis, was up on stage in his wig and crimson robe, the coat of arms behind him. The barristers, in wigs and gowns, were arranged in rows on the floor of the theatre, under lights. As they stood to make their speeches, the unavoidable illusion was created that this was a scripted drama, conceived by a playwright as an indictment of England’s archaic legal system.

Given the national outcry that the changing of statements had always caused, the prosecution seemed strangely lame. The opening speech by CPS barrister, Sarah Whitehouse QC, was restrained, and seemed to minimise the families’ outrage that the police had perpetrated a cover-up. She said the trial “is not about the causes of the disaster” or whose fault it was, but this was confusing, given her own allegation that the statements were changed to “mask the failings” of the police. It meant that original police allegations against supporters were read out in court without context or challenge.

Steve Kelly, who watched the live broadcast in Liverpool with dismay, wrote to Max Hill, the director of public prosecutions, after the trial. He described the prosecution as “a feeble effort,” saying he was “constantly in a state of shock” hearing the allegations, which he considered to be direct accusations against his brother Mike.

Hill has fully defended the CPS’s work, telling the House of Commons justice committee in June 2021: “I maintain that we did everything we could, and we applied all of the vigour that we could.”

The case did not even make it as far as being decided by the jury. The curtain came down on 26 May when Davis stopped the trial. He cleared Denton, saying that the chief superintendent had only been following advice from Metcalf, the solicitor, about having the police officers’ statements amended. The judge’s wider reasoning makes for a seriously concerning set of assertions about the law itself. The criminal offence of “perverting the course of public justice” could not have been committed by any of the three defendants, he ruled, because the Taylor inquiry, to which the amended statements were sent, was not a “course of public justice, like a court case”. But Popper’s inquest could not have been perverted either, because its scope was narrower before the Human Rights Act, Davis said. That appears deeply questionable, because Popper’s inquest did consider the circumstances of the disaster, dwelt on the police allegations particularly the claims about drinking, and the lord chief justice had quashed it in 2012 partly on the basis that the police case was false.

Davis also decided that the South Yorkshire police and Metcalf, as the force’s lawyer, had no legal “duty of candour” to the inquest, meaning they were not required to be fully open and truthful.

So the legal findings delivered as the final scene of the Hillsborough tragedy were these: police and their solicitor can falsify evidence to a public inquiry without committing a criminal offence, and they did not have to be wholly truthful to an inquest. Also, there was a section about a solicitor’s duties under English law, in which Davis noted that if a solicitor “realises that the court is acting on a false basis”, there is “no duty to correct the court or to draw the court’s attention to the true position”.

So, a solicitor can be aware that a miscarriage of justice is being perpetrated, and has no duty to correct it. Whitehouse rose and, to the families’ surprise, said the CPS was not going to appeal this ruling.

Up in the circle, Burke stood up, as she had in Preston when Duckenfield was acquitted, and in front of the jury, she said calmly again, that her father had been killed at Hillsborough, and that nobody had ever been held to account for it. Davis told her to sit down and be quiet.

The judge told the jury foreman to state formally that Metcalf, Denton and Foster were not guilty. And that was it. Thirty-two years of legal proceedings were over. After 97 people were unlawfully killed at an FA Cup semi final, and a major police force constructed a false case to blame the victims, nobody had been held to account. Only Mackrell, the former Sheffield Wednesday secretary, has been convicted, of a safety offence related to allocating only seven turnstiles for the 10,100 people with tickets to stand on the Leppings Lane terrace. He had been fined £6,500.

In the grey and unseasonal cold on the forecourt outside the Lowry, Burke, Hicks and the family of Brian Matthews, a married financial consultant who died at Hillsborough aged 38, stood and talked to the media, lambasting the ruling and the process. At a press conference outside Liverpool’s Anfield stadium, Aspinall, standing alongside Burnham, raged at what the families had been put through, calling it “a complete and utter disgrace”, and said the whole system needed to change.

Like many family members, Hicks reflects now that after so long a fight, she must now try to live her life.

“Who knows what was lost that day when my daughters didn’t come home? There may have been grandchildren, and their children. My daughters went to watch a football match and I feel like their lives were just ripped away, through the lack of police control.

“And these 32 years, what they put us through: I feel betrayed, by judges and by police. It has been a betrayal of everything I was brought up to believe about my own country. Your brain can’t compute why it’s acceptable in a British court to bring back evidence that was dismissed years earlier. The injustice and grief run alongside each other; it’s like a knife in your heart.

“We’ve fought for our own loved ones, but there has been a strong feeling of responsibility, too: that if there is no accountability, this can happen to other people.”