The Royal Mail (RMG), with us for more than 500 years, is loved and disliked by the UK public in equal measure. In the UK, it is a business clearly in need of modernisation that generates margins of only a little over 5 per cent. The European arm (more a courier than national mail carrier) makes closer to 10 per cent returns. Is sweeping modernisation set to drive up returns and make a great recovery story? Or is this people-heavy business going to struggle under the burden of high inflation? Even if margins do not materially rise in the UK, there is a case to be argued that this business is significantly under-valued within the group. Add in some generous dividends and there is scope for Royal Mail to deliver a lot of value.

Riding a wave

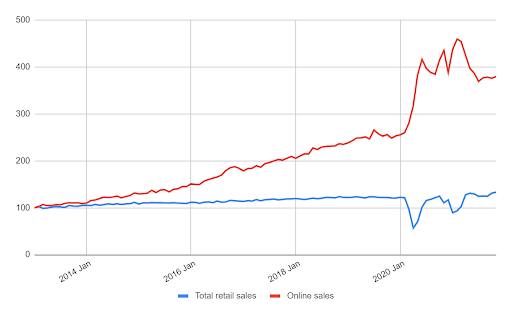

Covid has been a boon for delivery companies globally with shops closed for extended periods in the last two years and a reluctance by many shoppers to venture into crowded shops. The recent UK pre-Christmas footfall and sales data confirmed that while 2021 was better on the high street than the disastrous 2020 activity is still well below 2019. Overall retail sales in November were around 10.5 per cent higher than the same month in 2019, but in-store sales are around 15 per cent lower; in contrast online sales are 54 per cent higher.

Online sales are a little softer now than in the peak months of 2020 when stores closure were most acute. In November 2021, total online retail averaged £1.9bn per week against the mean £2.3bn achieved across the first quarter of 2020. This is reflected in Royal Mail’s recent first-half figures which reported lower parcel volumes year on year.

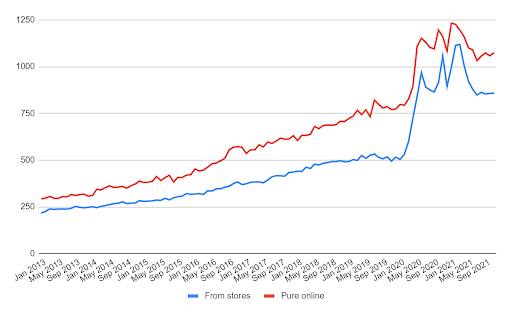

The real takeaway here, however, should be the long trend in online retail and the share that has been taken from stores. Covid has made online shopping incrementally more popular, but since the group’s IPO in 2013 to the start of Covid online retailing in the UK rose by 10.3 per cent CAGR. While that pace is unlikely to continue (in 2019 the rate of expansion slowed to 7 per cent) it is likely that online will take further share from stores as the high streets’ woes continue and grow much faster than underlying GDP for some time. All good news for the delivery industry.

One question investors need to ask is whether the boom in parcel deliveries in 2020 and 2021 was a pure Covid windfall or whether this will prove to have been something more structural: a permanent step-up. Windfall is regarded by equity markets as delivering lower quality earnings that can drag on a share’s rating. Covid has been an accelerant here and if one draws a straight line from 2013 to today, the long-term trend would have predicted c.£1.5bn of weekly sales online in 2021: sales are currently £1.93bn. So, does the step up from Covid hold or do online sales drop back to trend? That is hard to determine but is a pivotal question for investors of how much and when.

Long-trend vs actual for UK online retail sales – non-food

Source: ONS, Investors’ Chronicle

It is important not only to focus on the volume of retail sales but also shopping patterns and parcel type. In terms of pattern, retailers must accept that returns will be higher as shoppers unable to browse or try items will buy multiples and make more returns. That backhaul traffic is often free to customers but will have to be paid for by retailers. Also the average revenue per parcel (ARPP) is increasing due to size/weight and premium service levels (ie tracked or guaranteed) another positive for delivery businesses: Royal Mail reported that tracked et al parcel volumes rose 21 per cent in the first half, for example. In this year’s first half, UK parcel volumes fell by 4 per cent but revenues rose by 4 per cent.

Weekly online retail sales UK, non-food – seasonally adjusted £m

Source: ONS

Total retail sales vs online retail sales – index & seasonally adjusted

Source: ONS

Dead letter drop

A default assumption might be that letter sending is fading rapidly. However, despite letter volume falling 19 per cent versus 2019, revenue per item is strong due again to premium traffic. Also stamp prices are rising faster than inflation, (+8.5 per cent 2020 and 11.8 per cent 2021). UK postage is still cheaper than in many EU countries and customers seemed to be content to absorb these increases under the promise of improved service. That will need to be consistently delivered, however, if price momentum is to be sustained.

Cost pressures

Rising inflation is a problem for all businesses, but Royal Mail has a potential issue with its cost structure. Essentially half of its operating costs are staff costs and wage inflation is running hot. There is pressure on wages with the 2022 National Insurance increase set to cost £50m per annum and every 1 per cent of wage inflation hitting profits by another £40m. Historically, Royal Mail has simply hired more, temporary staff but in the pernicious post-Brexit, Covid and inflation environments, that is much easier said than done. In addition to a lack of available bodies per se, there is more intense competition for labour now from other courier businesses.

While there is a clear need to modernise and mechanise, unionisation has long been a barrier to progress for Royal Mail, a pressure point that other courier companies do not have. Royal Mail needs to modernise its parcel handling services in order to remain competitive and a 2020 trade union framework deal (“Pathway to change”) left Royal Mail with union support for modernisation but with no ability to make compulsory redundancies. Far from ideal but it did end an acrimonious two-year battle with key trade unions which was harming progress and profitability. Around £100m of annual savings are targeted from 2022 onwards.

The process of modernising the handling and distribution is in good hands. The new UK CEO (since January) Simon Thompson came from Ocado, who might be considered leaders in the field.

Distant shores

Royal Mail is more than just the UK national carrier and also has a sizeable international business today: GLS, the international parcels business. Based in Holland and covering north Europe and North America (following the purchase of Rosenau in October of £210m). GLS is more akin to a pure courier such as UPS or DPD, it is not a mail carrier and has a higher B2B bias than Royal Mail. The latter has allowed for more stable total volume and whereas the UK arm is down in 2021 year to date, GLS’s volume is 7 per cent up on 2020. While GLS has only around half the revenue of the UK arm, it has latterly reported similar profitability, underscoring the inefficiencies that remain to be addressed in Royal Mail.

Capital returns

In its November half-year results, Royal Mail announced a £400m capital return split 50:50 between a special dividend and a share buyback. While I believe that for the long-term good of the share price it would have been better to make the whole thing a buyback, this is a decent compromise. The special will have dented the share price in the usual way (they were marked ex-dividend of 20p on 2 December and dropped 20p) but the buy-back should bump EPS up by 4 per cent or c.2.9p and on a PE ratio of roughly seven times that broadly restore the equity value (2.9p x 7 = 20.3p). This means that the special dividend can be viewed as incremental income with no capital loss and augmenting the total return.

More important is that the special dividend may turn out to look and feel more of an ordinary dividend going forwards. It could have been seen as a single windfall distribution due to bump up in parcel volume but this is not the case. The board has stated that it wants to run close to a nil debt/nil cash balance sheet and as there is good free cash flow even after investment in UK upgrades, there is likely to be a similarly-sized, similarly-structured capital return in FY2023 and FY2024, possibly beyond. Even with the special included, dividend cover is still more than 1.5x. The core yield is forecast to rise to almost 6 per cent by 2024 and with the special dividend capable of being classed as truly incremental income (due to the buyback boost), the net income here over three years (at least) could exceed 10 per cent. One should normally run a mile from such apparent income levels but by using the partial buyback, the income is given far greater substance.

Unravelling the sum of the parts

A valuable way used by City analysts to expose value in a business is to use a sum-of-the-parts (SOTP) calculation. Where a business has distinct parts, the various parts can be valued using peer group valuations and the aggregation of these values compared with the market capitalisation of the whole business.

In many cases, this process highlights that one part of a group is carrying a low implied value and that is the case with Royal Mail. If the GLS operations (the most stable and ‘issue free’ part of the group) is valued on the same basis as its rivals, the difference between this valuation and the market capitalisation has to be the implied value for the UK operations. Debt or net cash can be ignored as we are heading for an ungeared balance sheet due to the capital return. This implied value can then be compared to the profitability to show an effective valuation multiple. From the table below, the implied, current valuation for the UK business is just two times on an EV/EBIT basis, which equates to a PE ratio of less than four times. This level of valuation normally accompanies either ultra-low earnings quality, short-term windfall profits or a business facing a profit collapse.

While there are issues with wage costs, some questions over the sustainable level of parcel volumes in a non-Covid world and letter volumes are in terminal decline there is now clear water to make efficiencies with the Pathway to Change framework and parcel volumes are on a growth trend, as is ARPP. UK growth may not be spectacular but Peel Hunt believes EBIT here can grow 10-15 per cent from 2022 to 2024 even after factoring in heavier employment costs. On that basis, the implied valuation is too severe.

Even if one keeps the rating for the UK arm low (say 4-5x EV/EBIT and half the likely value of GLS) this could leave the shares under-valued by >£1bn or >100p a share. If one can overcome long-held views of this as a troubled, somewhat backward business there could be some pretty decent value here.

Royal Mail group sum of the parts

|

Input values |

Derived value |

|

|

GLS – 10x EV/EBIT |

£3,710m |

|

|

Royal Mail UK |

£1,174m |

|

|

Net cash |

£61m |

|

|

Group valuation/Market Cap |

£4,945m |

|

|

Royal Mail UK EBIT |

£566m |

|

|

Implied EV/EBIT multiple |

2.07x |

Souce: Royal Mail, FactSet, Investors’ Chronicle, Peel Hunt forecasts

Source link