The new postage stamps bearing the image of King Charles III were released by the Royal Mail this week.

The simple picture shows him without a crown, with a company executive describing this as a “defining part” of his reign.

David Gold, Royal Mail’s director of external affairs and policy, said they received guidance from the King to maintain “continuity” and the new stamp came with his personal approval. Gold welcomed the decision not to wear a crown. He said it amounted to King Charles declaring “’this is me and I’m at your service’, which I think in this modern age is actually rather humbling.”

The King’s intention of showing he shares a common humanity with his subjects is plain. But what if the wearing of a crown is itself the biblically-based act of humility?

In the Bible, the focus of the crown isn’t about the person or the attributes of the monarch – it’s a symbol pointing to where authority comes from. In this, the crown and the other regalia the King will bear during his coronation and reign, are symbols that all authority comes from God.

In the Bible, the crown is a symbol pointing to God’s ultimate authority

Throughout history, crowns were an image of authority and honour, as God is the one who crowns kings. All earthly authority comes from heaven (Romans 13:1-2) and this continues to be recognised in the hybrid, uncodified constitution of modern-day Britain, written in law, precedent and Christian ceremony. Even with an elected Parliament, the principle is recognised by MPs and peers submitting themselves to Christ in prayer every day, across both chambers.

In David’s psalm describing the king, it is said that God “welcomed him with the blessings of good things and set a crown of fine gold on his head” (Psalm 21:3). A right understanding of the King’s crown is that it is a symbol of his representative rule over a kingdom ultimately ruled by God. The ancient idea that continues into the present age is that God is the only true authority, the everlasting King.

This is why the Bible speaks of a day when we will see Christ with many crowns on his head, an image of his ultimate authority (Revelation 19:12). This carries through in the imagery of the elders in Revelation laying their crowns before the throne and declaring “glory and honour and power” belong to God.

When the ancient kings of the different parts of England embraced Christianity, they looked to the Old Testament on how to build their kingdoms. By swearing covenantal promises to acknowledge Christ’s reign and God’s law, they hoped to enter into the same blessings as Israel. They did this by oaths and acts of consecration, such as crown-wearing. This is why so much of what jurist A.V Dicey called the “dignified parts” of Britain’s constitution, operative in the coming coronation of the King, are lifted straight from the Bible. They are sacramental means of providing God’s grace to the body politic. The nation’s leaders also make their own oaths that recognise Crown authority (2 Kings 11:12,17).

In ‘The coronation: history and ceremonial’ (House of Commons Library), the ancient role of the Church in England is set out: “In England, the main elements of a coronation service can be traced to the ceremony devised by Saint Dunstan for King Edgar’s crowning at Bath Abbey in 973.” Today, no other monarchy in Europe continues with the order of Christian symbols and ceremony that has been used in England for over one thousand years.

The moment in the coronation involving “unction” – the act of anointing a monarch with holy oil – can be traced back to the 7th and 8th centuries. The Commons’ briefing adds, “This act of anointing, wrote Thomas Asbridge of Richard I’s in 1189, ‘was the coronation’s central drama – the moment at which Richard was deemed to have been remade as a divinely ordained king: God’s chosen representative on Earth.’”

After the anointing, the ceremony leads to the crowning and then a Benediction. So at the coronation in 1953 of our late Queen Elizabeth II, the Archbishop said a prayer beginning with the words “God crown you with a crown of glory and righteousness”, with the choir then singing the anthem ‘Be strong and of a good courage’. By contrast, in largely pre-Christian times in ancient Britain, kings had a helmet placed on them at their coronation – an earthly symbol of military power and strength.

One Christian political tradition in Britain holds to the biblical view that the terms of such covenants are conditional (Proverbs 27:24). God removes the crown if a King and the nation’s leaders with him fail to maintain the promises they have made.

Psalm 89:39 reflects, “You have renounced the covenant with your servant and have defiled his crown in the dust.”

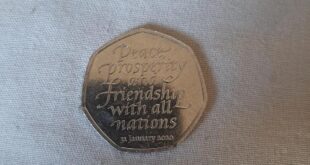

From this perspective, casting away a crown – not that Charles intended this – looks like an accidental repudiation of the Christian and constitutional understanding of biblical humility.

Source link