What’s the term for when a ransomware group blames a geopolitically awkward attack it appears to have carried out on someone – anyone – else, just not them?

See Also: Live Webinar | Navigating the Difficulties of Patching OT

Let’s call it getting “Colonial Pipelined,” after the DarkSide group’s disastrous hit on that oil pipeline system led the crime group to kill its brand.

Is the same about to happen to LockBit? The prolific ransomware group has been tied to the recent disruption of Britain’s national postal system. On Wednesday, Royal Mail warned that it was unable to send any letter or parcels abroad due to a “cyber incident,” apparently so described because the cause of the system outage wasn’t immediately clear.

What is evident is that the incident has been preventing Royal Mail from sending any letters or parcels abroad. As of Friday, the problem had yet to be resolved.

Citing sources with knowledge of the investigation, on Thursday Britain’s The Telegraph newspaper and later the BBC reported that the attack appears to trace to LockBit.

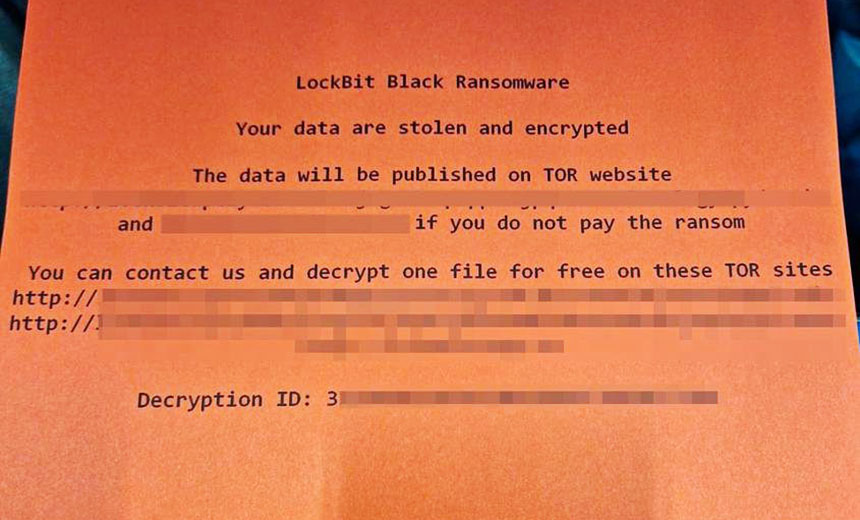

Security experts report that ransom notes recovered from the attack are labeled as being from LockBit Black, aka LockBit 3.0, which is the gang’s current name for itself. U.K.-based CISO Daniel Card reports that the ransom note lists links to payment and negotiation pages reachable via Tor – denoted by their having .onion URLs – that match links previously used by LockBit 3.0.

LockBit’s dedicated data leak site doesn’t list Royal Mail as a victim. But groups don’t list all ransomware victims on such sites, even if they don’t pay. The primary function of such sites is to try to “name and shame” victims into paying, and only after they fail to commence negotiations or pay a ransom within an agreed time frame. Some groups, such as LockBit, increase the pressure by including a countdown timer counting down until they’ll release data allegedly stolen from a victim if that victim doesn’t pay.

LockBit Claims: It Wasn’t Us

Royal Mail’s absence from LockBit’s data leak site may also be explained – at least indirectly – by LockBit representative LockBitSupp claiming to Bleeping Computer that his group wasn’t behind the attack. Instead, he’s pointed the finger at someone, identity unknown, who used an old, leaked copy of LockBit’s builder, which is software for generating fresh versions of its ransomware executable.

Color security experts as skeptical. “Yes, that public-facing representative of the LockBit ransomware gang never lied before and also will never lie, so just trust what he said,” tweets the anti-ransomware research group MalwareHunterTeam (see: Secrets and Lies: The Games Ransomware Attackers Play).

As Card reports, the .onion links in the ransomware note trace to previously seen ones used by LockBit. If someone else used an old, leaked builder for LockBit, why didn’t they update the negotiation and payment links in the ransomware note to go to Tor sites they controlled, so they would receive any ransom paid? An alternate theory is that a nation-state used LockBit’s leaked builder as a NotPetya-inspired wiper to attack a Royal Mail facility. But that seems unlikely.

Will LockBit Get Burned?

While LockBit claims on its data leak site that it is based in the Netherlands, Jon DiMaggio, chief security strategist at Analyst1, says that like many ransomware operations,LockBit is based in Russia. Unlike many other ransomware groups, it has enjoyed unusual longevity, in part due to its relentless focus on building easy-to-use and highly automated tools (see: Keys to LockBit’s Success: Self-Promotion, Technical Acumen).

LockBit is a ransomware-as-a-service operation, meaning it leases its crypto-locking malware to business partners – aka affiliates – in exchange for a cut of the proceeds, and affiliates keep up to 75% of every ransom a victim they snare pays.

“It is extremely prolific,” says Louise Ferrett, a threat intelligence analyst at Searchlight Security. “LockBit was the most commonly used RaaS in 2022,” based on counting known victims, which number 1,300. “Its affiliate model means that it has victims across most industries and around the world,” she adds.

The group has managed to avoid some of the poor choices made by other major operations, which turned them from “must partner with” options into liabilities.

Unlike REvil, aka Sodinokibi, LockBit’s infrastructure doesn’t appear to have been infiltrated or seriously messed with, as REvil’s was after it made a string of high-profile hits, including disrupting the world’s largest meat processor, JBS, as well as IT management software vendor Kaseya. LockBit also avoided emulating Conti’s disastrous decision to publicly back Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, leading to its operators spinning off new groups and retiring that brand.

But the Royal Mail attack has strong parallels with the Colonial Pipeline hit. When the DarkSide group attacked the pipeline in May 2021, the resulting disruption in systems led to Americans panic-buying fuel. Facing a national security furor, the operators of DarkSide attempted to blame the attack on an affiliate who had gone rogue (see: Ransomware Groups Keep Blaming Affiliates for Awkward Hits).

DarkSide’s damage control effort failed. Shortly thereafter, it disappeared. While the group has subsequently rebranded and respawned as BlackMatter, and later as Alphv, aka BlackCat, having to pause and reboot must have taken a bite out of profits, not to mention painting a target on operators’ backs and driving away would-be affiliates.

Will Royal Mail be the attack that now dooms LockBit?