Before email put them at risk and smartphones became an existential threat, handwritten letters played a vital role in everyday life. They could be used to declare love to a partner, or convey news of a tragedy. They united penpals from around the world. Sometimes, grandma slipped money into them.

“Letter writing is an expression that is necessary for wellbeing and I feel that digital communication takes that away,” says Melanie Knight, an avid letter writer from Melbourne.

This week, Australia’s government-owned postal service sounded an alarm for letter writing after reporting a $190m loss in its letter business over a six-month period. Every year it is costing Australia Post more to deliver fewer letters as a growing population demands more delivery points.

The chief executive of Australia Post, Paul Graham, said there are concerns over the viability of the letters business and that all options were on the table, including reviewing the frequency of deliveries.

The postal service expects the “unstoppable decline” will gather pace, making letters a peripheral form of communication by 2030.

Knight, an expressive arts therapist who runs creative letter-writing workshops, says society will be poorer for its demise.

“Even though there’s thousands of emojis, [digital communication] is so homogeneous,” Knight says.

“The way I might choose to share, from minutiae and mundane to something that feels very big and profound, just comes out so differently when you sit down and really pick the words that go down on paper instead of using your thumbs.”

Rewind three decades, and the letter delivery business was booming. In the 1990s, letter volumes grew in tandem with Australia’s economic progress, increasing by 5% a year, according to an analysis of Australia Post financial reports.

Mail volumes hit a high point of well over 5bn in 2007-08 when the basic postal rate was 50c. But the global financial crisis and the surge in popularity of text messaging and public webmail services like Hotmail prompted an irreversible change in behaviour.

Australians switched to convenient and cheaper communications. Letter volumes at Australia Post have fallen ever since, diving to just 1.6bn in 2021-22.

The letter delivery unit has become a significant weight on the business, and is set to drag the postal service into financial loss by the end of June, despite its recent increase in the basic stamp price to $1.20.

“We expect annual volumes will decline further, with Australian households receiving less than one letter per week by the end of the decade,” Graham says.

Postal services around the world are grappling with the same problems; some have been privatised amid heated political debate, while others are reducing the number of days they deliver letters.

France’s La Post has moved to a three-days-a-week letter delivery service, with a creative next-day option whereby customers send an email to the postal service, which is printed and delivered.

UK’s Royal Mail has asked the government to switch letter delivery from a six-days-a-week service to five – in line with Australia – but the request has faced resistance from some government ministers.

The US Postal Service has been at the centre of years of political fighting that has delayed attempts to modernise. Supported by a reform package signed last year, the US mail agency now plans to buy 66,000 electric vehicles over the next five years to replace its ageing trucks and improve finances.

In Australia, domestic letters now contribute less than 20% of revenue to the postal service, making it more fitting to describe Australia Post as a parcel and services company that also delivers letters, given package deliveries generate far more revenue. Part of the decline in letter deliveries is also linked to an electronic shift by businesses where, for example, bills can be sent and paid for online.

Sign up to Guardian Australia’s Afternoon Update

Our Australian afternoon update email breaks down the key national and international stories of the day and why they matter

after newsletter promotion

Most postal services around the world are cutting staff and reducing the number of their physical properties and post offices.

Australia Post describes the current state as “unsustainable”, and has a plan of simplifying its products and services, and creating a viable letters service. It has not been drawn on specific cost-cutting initiatives and the potential impact on a workforce of more than 36,000.

Any significant changes would need to go through its sole shareholder – the government.

Peter Slattery, a research fellow at Monash University, says he sees a future role for physical letters even if more generic correspondence goes digital.

“Both in the business world and the personal world, letters will be associated with high-value, selected communication and more of the mass communication will switch to digital,” says Slattery, who writes on behavioural science.

“People value getting a letter a lot more; they know it takes more effort and feels more tangible.”

This may include an annual handwritten letter from a business to its most valued clients, creating a point of difference to the mass of online correspondence, he says.

Letter volumes also get a boost during elections and national events like the census. The 2022 federal election triggered 107m letter deliveries, Australia Post data shows, and 2.3m returned postal votes.

However, the spikes in letter deliveries tied to special events do little to dent the broader downtrend, which means receiving a personal letter will become all the more rare in the years to come.

Some fear the transient nature of digital communication means future generations will miss out on having documented insight into the minds of notable figures, such as the thoughts contained in archived love letters from Johnny Cash to June Carter, Napoleon to Josephine and Elizabeth Taylor to Richard Burton.

“Letters are so precious, they can give a really personal lens into a period of time through lived experience,” says Knight.

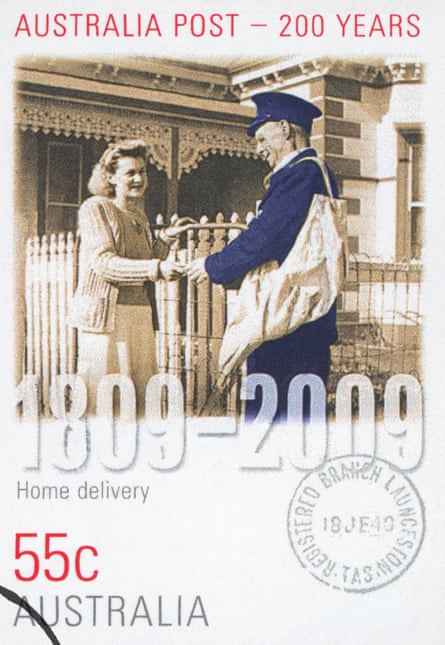

“I hope we don’t lose that. What it’s like to walk down the driveway and open the mailbox and find a personal letter there – it’s just thrilling.”

Source link