The scene was a memorial service at the Guards’ Chapel, across the road from Buckingham Palace and one of the smartest places for a send-off London has to offer.

But according to Tina Brown, who was there to pay her respects to the debonair Lord Lichfield, fashionable photographer to the demi-monde, glamour was sadly absent.

In its place she sniffed ‘the creak of irrelevance and decay’.

The pews, she noted were filled with ‘Court Circular stalwarts’. There was a ‘dowdy and gruff’ Princess Anne, the Duchess of Cornwall in a ‘dour air stewardess suit’,

Camilla’s ex-husband Andrew Parker Bowles resembling a ‘walking pink gin’ and a ‘decrepit Lord Snowdon’, the Queen’s former brother-in-law, displaying ‘a bad-tempered air’.

Even the younger generation back then in 2006, ‘pale and discontented’, did not escape her forensic gaze.

Every time one rose to speak, the sage at her elbow, the Queen Mother’s former factotum William ‘Backstairs Billy’ Tallon hissed something pejorative.

Only the imperious Princess Michael of Kent offered a frisson of allure.

Brown found herself longing for the ‘tall, blonde glory of Princess Diana to appear in a blaze of paparazzi’.

But Diana was long dead and a deep dullness had settled on the Royal Family, for which they were eternally grateful.

Prince Harry has become increasingly isolated from the Royal Family since his relationship with Meghan Markle, but Brown says this began before he met the actress

‘Never again’, was the mantra. ‘We don’t want another Diana’ was the refrain that echoed from the highest reaches of Palace life.

Twenty five years after the princess’s tragic, unexpected death, the formidable Ms Brown, author of the explosive Diana Chronicles, which was an early Naughties sensation, has returned to the fray.

Her new book, The Palace Papers: Inside The House Of Windsor — The Truth And The Turmoil, examines how that quest to ensure the monarchy is not simply a platform for family members to seek public acclaim has turned out.

Even a cursory look at the royal landscape would suggest things have not gone entirely to plan.

The book reveals how the Queen vanquished the ghost of Diana by saying she wanted Camilla to become Queen when Charles takes to the throne

Just this week, Harry and Meghan — with Netflix crew dancing attendance — have lobbed another of their televisual truth bombs after the prince declared he wanted to make sure his grandmother was ‘protected’.

With added bombast, he let it slip that he enjoyed a special relationship with her unlike any other, that the two could ‘talk about things she can’t talk about with anybody else’.

Meanwhile, the dust has scarcely settled on the disgraced Duke of York’s £12 million out-of-court agreement of a sex-abuse lawsuit.

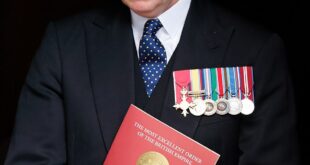

And less than a month after escorting his mother to Prince Philip’s thanksgiving service, Andrew, the royal pariah, is said to be angling for a return to public duties, despite the shame of his links to the notorious paedophile Jeffrey Epstein.

‘Friction between the brothers escalated over their professional alignments,’ Brown writes. ‘William knew he had to be respectful of hierarchy when it came to his father’s ownership of the environmental platform, but he was less willing to accede to his brother’

As ever, the devil is in the delicious detail, from Harry’s mental health struggles and the girl who put him on the path to treatment, to the Queen’s remarkably with-it grasp of cultural niceties.

Asked if it was OK if the heavy metal rocker Ozzy Osbourne could appear at the 2002 Party at the Palace to mark her Golden Jubilee, she replied dryly: ‘As long as he doesn’t bite the head off a bat.’

While no conventional royal historian, Brown tackles her subjects with the same brio she brought to her years as a highly regarded magazine editor, first with Tatler, then with Vanity Fair and the New Yorker.

Her access to those who flit around the royals gives her writing an edgy authenticity.

The book, she says, is the result of two years’ work — and impeccable sources.

‘I talked to more than 120 people, many of whom have been intimately involved with the senior royals and their households during the turbulent years since Diana died,’ she explained.

The result is a tour d’horizon of the recent travails of the Royal Family, which is both critical of and surprisingly sympathetic to the figure at the heart of the story: the 96-year-old Queen, whose head-in-the-sand approach or ‘ostriching’ she often mocks.

Some are bound to be upset at Brown’s frank, almost cruel assessment of Diana in the final months of her life after her Panorama interview.

Following recent revelations about Martin Bashir’s deceit in securing his interview, Brown claims Diana had no regrets about the collaboration.

‘I don’t subscribe to the now pervasive narrative that Diana was a vulnerable victim of media manipulation, a mere marionette tossed about by malign forces beyond her control,’ she says.

‘I find it offensive to present the canny, resourceful Diana as a woman of no agency, as either a foolish, duped child or the hapless casualty of malevolent muckrakers.’

She quotes cordless phone magnate Gulu Lalvani, who briefly dated the princess in early 1997, saying that Diana told him she had said exactly what she wanted to say in the broadcast.

‘She was pleased about it,’ Lalvani told Brown.

‘She didn’t have a bad word to say about Martin Bashir. She realised it served her purpose.’

I, for one, disagree. Not only did Diana fall out with Bashir, she told me she fervently wished she had not spoken about her betrayed love for Army officer James Hewitt because it had damaged her relationship with William and Harry.

Recalling her own lunch with Diana in New York six weeks before the princess’s death, Brown admits she was ‘bowled over’ by her confidence.

‘Diana was always more beautiful in person than in photographs, the huge, limpid blue eyes, the skin like a freshwater pearl, the supermodel height that was even more imposing in three-inch Manolos.

‘She told us her story of loneliness and hurt at Charles’s hands with an irresistible soulful intimacy . . . then switched to a startlingly sophisticated vision of how she planned to leverage her celebrity for the causes she cared about.’

Her plan, says Brown, ‘sounds very like what Meghan and Harry are attempting with their entertainment deals today, but with one central difference: it was better thought out.’

So what other intriguing nuggets does the book contain?

Frictions between brothers escalated

Brown considers Harry’s departure from royal life to be a huge loss, not just to the nation but also to the one person who needs him the most: his brother William, the future king.

Intriguingly, she says that the relationship between the two siblings began to decline long before the destabilising arrival of Meghan Markle.

‘Friction between the brothers escalated over their professional alignments,’ Brown writes.

‘William knew he had to be respectful of hierarchy when it came to his father’s ownership of the environmental platform, but he was less willing to accede to his brother.’

For his part, Harry felt William was ‘hogging the best briefs’, a rivalry especially keen over their joint interests in Africa and conservation.

Brown claims that Harry wanted the prestigious rhino and elephant charity the Tusk Trust, of which William had been patron since 2005.

‘Harry was a very, very angry man. I think those were absolutely Olympic rows,’ she quotes a friend of the brothers as saying.

It didn’t help that Harry had a more natural, less formal way with the public.

‘If William makes a speech, everything from “Good evening” onwards has to be typed out and handed to him,’ a charity official tells her.

‘When he came to our dining club one evening, as soon as he got up to speak he froze.’

Harry knew how to work a room like his grandfather Prince Philip, starting with a joke to break the ice.

But if Harry was discontented over his royal duties, he was even more unhappy about the state of his love life.

After Harry’s split from aristocratic actress Cressida Bonas in 2014, Brown quotes Prince Charles telling a party guest: ‘I don’t know what to do about Harry. We so miss Cressida.’

Cressie, as she is known by family — the willowy blonde daughter of Lady Mary-Gaye Curzon — found her royal boyfriend both sweet and tiresome.

His mood was often confrontational.

‘When he wasn’t venting about William, he was pouring out resentments about Charles,’ Brown writes.

Father and son communicated mostly through their private offices.

One ‘disgruntled’ episode concerned the prince’s offer of a 30th birthday present for Harry.

‘Would you like another dinner jacket?’ Charles asked.

Harry said: ‘OK’.

Brown reports a source: ‘So the man from Savile Row came to measure him and when the suit arrived . . . one arm was shorter than the other and one leg shorter than the other, so it was . . . returned in a box, which seemed kind of analogous to their whole relationship.’

Cressida Bonas, pictured here in 2019, found her Prince Harry to be both sweet and tiresome during their relationship, Brown says

This, Brown describes as ‘no communication, and when there was, it went wrong’.

Meanwhile, Cressida, a normal 25-year-old, found Harry’s resentment towards the media trying.

She ‘wanted to go out to dinner and touch knees under the table,’ a friend tells Brown.

‘Harry would walk four paces ahead of her, instead of holding her hand. When they went to the theatre, he left at the interval to get out without a hassle.

‘She was either being dragged through the streets being yelled at or ignored while he threw a hissy fit.’

While media reports talked of her romantic love affair with the prince, the ‘bizarre reality of date nights was glumly eating takeaway and watching Netflix at Nottingham Cottage, Harry’s none-too-tidy two-bedroom grace-and-favour bachelor pad in the grounds of Kensington Palace’.

Cressida became increasingly concerned about Harry’s mental health.

According to Brown, it was Cressie who first persuaded him to see a therapist. To find the right person, he took advice from MI6.

‘There was a need for someone who would be incredibly discreet and who understood what it’s like to have a public version of your life and a private version of your life,’ Brown quotes a contact.

‘Therapists at MI6, that’s what they do.’

His relationship with Bonas did not survive, however.

Brown reveals that after they parted Harry wrote Cressida ‘a sweet letter saying “I admire you, I wish you well and above all thank you for helping me to address my demons and seek help” ’.

Meghan wanted leading lady status

Meghan Markle’s arrival in Harry’s life changed everything almost overnight.

She and the prince became ‘drunk on a shared fantasy of being the instruments of global transformation who, once married, would operate in the celebrity stratosphere once inhabited by Princess Diana’.

The world caught a glimpse of this power grab at the unveiling of the so-called ‘Fab Four’, when Meghan articulately spoke with all her actressy skill at a meeting of their Royal Foundation, which had set up the Heads Together mental health charity.

‘Harry looked on with awe and his brother and Kate stood by with expressionless irritation,’ Brown writes.

‘When it was Kate’s moment to speak, she was strikingly less articulate, as well as brief.’

Yet, Brown says, few knew that it was the Duchess of Cambridge who had been the prime mover in the mental health campaign, after years of providing emotional support for her brother, James Middleton, as he struggled with clinical depression.

So far so glamorous, but what Palace insiders saw as Meghan’s ‘wilful blindness to institutional culture’ was a clash with the actress’s world view.

‘In the ranking system of the entertainment world, star power — wattage — equals leverage . . . Alas, she seemed oblivious to the one critical factor that would determine the outcome of her plans for the future: primogeniture.’

For all his easy-going charm and huge popularity, Harry was not heir in line to the throne; he had slipped to sixth and, as Brown notes ‘when Kate became Queen, Meghan would have to curtsy to her’.

In the book, Brown shines a fascinating and waspish light on Meghan’s life just as she was meeting Harry and how her then blog, The Tig, was a dragnet for luxury freebies.

‘She won a reputation among the marketers of luxury brands of being warmly interested in receiving bags of designer swag.’

A publicist is quoted as saying she had been copied in to a message from a member of Meghan’s team after she became Duchess of Sussex.

‘Make sure [the publicist] knows that she can still send me anything. She’s always been one of the good ones.’

Brown offers a Hollywood insight into that famous three-way row between Harry, Meghan and Angela Kelly, the Queen’s dresser and assistant, over the choice of tiara to be worn at the wedding.

‘Meghan did not — or could not — perceive the difference between the Queen’s personal aide and a contract stylist at NBC Universal.’

With his rows over ‘what Meghan wants, Meghan gets’, Harry, she said, had morphed into ‘groomzilla’.

An aide is said to have described their confrontational stance as a mutual ‘addiction to drama’.

Harry was convinced that fellow family members were jealous of the Sussexes’ overseas appeal — just as they had once been of his mother, Brown writes

By the time the couple returned from their hugely successful Australia tour in late 2018, Harry was convinced that fellow family members were jealous of the Sussexes’ overseas appeal — just as they had once been of his mother.

But while after her first tour Diana realised the responsibility and duty that came with the intense interest she generated, Meghan appeared to draw a different conclusion.

Her view, according to Brown, was that ‘the monarchy likely needed her more than she needed them.

‘She had starred in the equivalent of a blockbuster film and wanted her leading-lady status to be reflected in lights’.

Andrew holed up in his bedroom

On Prince Andrew, Brown rarely pulls her punches, labelling the Queen’s favourite son a ‘coroneted sleaze machine’.

She describes with barely disguised contempt how, soon after his separation from Fergie, the Duke of York made a private visit to the Palm Springs estate of a former U.S. ambassador to Britain, where he ‘holed up in his bedroom for two days, apparently watching porn’.

Of his ten-year role as UK trade ambassador, Brown writes scornfully: ‘A string of international lowlifes, who had nothing to do with British diplomacy and everything to do with unsavoury personal deals that he was pursuing on the side, filled the Duke of York’s otherwise sparse calendar’.

As for Jeffrey Epstein, Brown says he referred to Andrew as ‘an idiot’ behind his back — ‘but to him a useful one’.

Epstein, she asserts, ‘made Andrew feel he had joined the big time — the deals, the girls, the plane, the glittering New York world, where he wasn’t seen as a full-grown man still dependent on his mother’s Privy Purse strings or on the pecking order of the palace.

The duke was always as oversexed as a boob-ogling adolescent’.

William and Kate’s secret lives

Brown relates how at a glitzy fundraiser for East Anglia’s Children’s Hospices, where Kate serves as royal patron, William transformed from star guest to ministering waiter.

Told that the evening’s ‘highest roller’ was too ill to join the dinner, the prince asked for a pot of tea on a tray and went and knocked on her door.

‘She was so over the moon,’ said investment banker Euan Rellie.

‘Hard not to be,’ writes Brown.

‘It was a gesture that showed the imagination and empathy of his mother.’

For history of art graduate Kate, secret visits to museums and art galleries are said to ‘nourish her inner life’.

Brown relates how the late QC Jeremy Hutchinson, viewing a Hockney exhibition at the Royal Academy at 8am one morning, was taken aback when the duchess took a seat beside him.

‘I miss my history of art,’ she told him. ‘It’s what I do to get my fix.’

The Palace Papers by Tina Brown is published next week by Century at £20. Tina Brown will be in conversation with Pandora Sykes at Conway Hall, London on Tuesday, May 3. Tickets available at howtoacademy.com

Source link