England’s Great Train Robbery was a complex heist carried out by a gang of 15 men, but only one among them was the subject of a film—Ronald ‘Buster’ Edwards.

“A robbery has been committed and you’ll never believe it – they’ve stolen the train!” This was the unforgettable line broadcast over the police’s VHF radio at 04.20am on the morning of 8 August 1963, the first alert in the wake of what came to be known as The Great Train Robbery.

However, it wasn’t the train the gang of 16 thieves were after, so much as the stg£2.6m (the equivalent of $7m in those days) that was on board. While a large gang was necessary to pull off the ambitious heist, some of the characters were more memorable than others, and none more so than Ronald ‘Buster’ Edwards, immortalised in the 1987 film ‘Buster’, with musician Phil Collins playing the title role.

Early life in London

Ronald Christopher Edwards was born on 27 January 1932 in the South London district of Lambeth. He came from a working-class background; his father was a barman, and he went to work in a sausage factory after leaving school. He immediately fell into criminal ways, stealing meat from the factory to sell on the black market in the post-World War II years. He did national service in the Royal Air Force, but couldn’t keep out of trouble, and was caught stealing cigarettes. When he returned to South London, he ran a drinking club and turned to a life of crime. He married his wife June Rose in 1952, and they had a daughter, Nicola (known as Nicky).

The Great Train Robbery was not Buster’s first time at the rodeo. He was thought to have been involved in the theft of £62,000 (worth £1.33 million today) from Comet House, the headquarters of British Overseas Airways Corporation at Heathrow Airport, in 1962. Many of the gang were captured, but Buster managed to escape arrest. Some of the other ‘alumni’ from this heist also went on to be involved in the Great Train Robbery.

Ronald ‘Buster’ Edwards.

They’ve stolen the train!

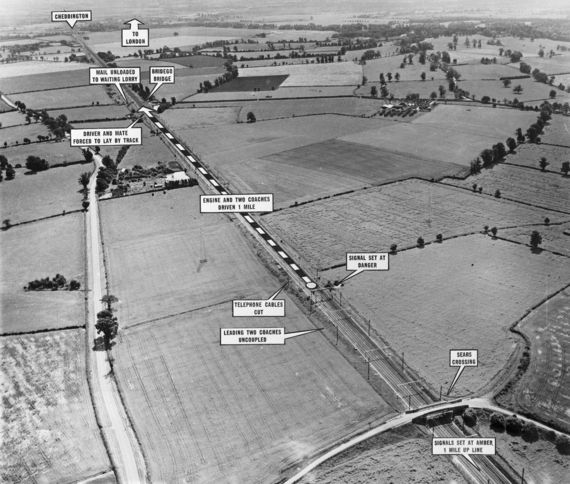

The gang intercepted the Glasgow–London mail train in Buckinghamshire in the early hours of 8 August 1963. The train ran overnight from Glasgow to London, delivering and taking on sacks of mail as it went. The carriages contained employees of Royal Mail, sorting the post as the train sped through the countryside. The second carriage behind the engine contained all the high-value packages (HVPs), but in those days it had very little in the way of security.

The gang tampered with the signal lights on the railway line, covering the green light and hooking up a battery to the red light, causing the train driver to bring the train to a halt. The driver was overpowered and beaten, and the robbers took just the engine and second carriage half a mile further along the track to the point where they had army vans waiting to unload the mail bags into.

Sticking to a tight time schedule they removed all but 8 of the 128 sacks from the HVP carriage and made off to a property 27 miles away; Leatherslade Farm had been purchased in advance for a hideout location. Listening in to the police VHF channels to see if the alarm had been raised, they soon figured out that the police would be searching the area, and they would have to get moving sooner rather than later—but not before they had some time to while away, famously using real cash to play Monopoly.

Loco in Acapulco

Most of the gang were soon captured, tried, and imprisoned, but Buster evaded arrest, along with his £150,000 share of the stolen money. In fact, much of the money was never recovered.

Buster and another leading gang member, Bruce Reynolds, took their families to Mexico, leading extravagant lifestyles—summed up neatly by one of the most memorable songs from the soundtrack of the movie ‘Buster’, the catchy Four Tops’ track ‘Loco in Acapulco’.

Eventually, the money ran out, and Buster’s family became homesick, so he negotiated his return to England in 1966. He surrendered and was sentenced to 15 years in jail. He was the 14th person to be convicted for their part in the robbery—in 1964, 13 men received prison sentences of up to 30 years for their various roles.

Going straight

Upon his early release from prison, in 1975, he tried to stay on the right side of the law and ran a flower stall at Waterloo Station. In a magazine interview, he gave an insight into the challenges of going straight after the thrill of a life of crime. “I know I’m lucky to have got a chance to have this stall and be my own boss but it’s so dreary compared with the life I used to lead,” he said. “It wasn’t even the money. I’ve been on jobs that haven’t netted me a penny but, oh, does the adrenaline flow.”

Somewhat ironically, he was himself the victim of a theft—although on a much less grand scale. In 1991, the British actor Dexter Fletcher scooped up two bundles of flowers from the stall as he ran by. For this paltry theft (to the value of £5), Buster reported Fletcher to the police (recognising him from the film ‘The Rachel Papers’ which he had seen just days before). Fletcher was arrested and charged; appearing at Horseferry Road Magistrates’ Court he pleaded guilty and was given a conditional discharge for twelve months and ordered to pay £30 costs. In mitigation, Fletcher said that the flowers were for his then-girlfriend and co-star Julia Sawalha, but that he had lost his bank card and had no money to pay. Fletcher subsequently apologised to Edwards and compensated him for the flowers—he went on to appear in Guy Ritchie’s gangster movie Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, and most recently directed the Elton John biopic Rocketman!

A tragic end

Later in life Buster developed acute depression, exacerbated by a severe alcohol problem. After two failed suicide attempts, he was found by his brother hanging from a steel girder in a lock-up garage in Leake St, Lambeth. He was aged just 63.

At the time of his death, he was under pressure due to an investigation by the police as part of an inquiry into a suspected large-scale fraud. His elaborate funeral was attended by some of London’s most notorious career criminals—two of the nine surviving train robbers and Charlie Kray, elder brother of the Kray twins.

During the inquest into Buster’s death, the coroner, Sir Montague Levine, was told that he was drinking a bottle of vodka a day. Medical reports noted his family had “been at the end of their tether” trying to stop him drinking.

At the time of his death he had enough alcohol in his body to kill someone unused to drinking, the court was told. A small bottle of vodka, one-third full, was found discarded by his body. Tragically, the pathologist, Dr Vesna Djurovic, surmised he had died just before he was discovered. Southwark Coroner’s Court recorded an open verdict, based on testimony that Buster had been too intoxicated to form an intent to kill himself. Buster’s wife June was too distressed to attend the hearing, and his daughter Nicola had to leave the room during the pathologist’s evidence.

And there his story ends with one last touch of style, as his family was collected from court by a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce with heavily-tinted windows.